Chronicles of a European Day of Jewish Culture in Italy

September 19, 2025

Sharks, Conspiracies, and Old Hatreds: The Mechanics of Disinformation

| About the author: Melissa Sonnino has been part of CEJI – A Jewish Contribution to an Inclusive Europe since 2011. As Director of the Facing Facts Network, she leads programmes on hate speech and hate crime, facilitating learning and exchange between civil society, public authorities and International institutions. She also served as senior researcher for the NOA research in Italy. |

At this year’s European Day of Jewish Culture, dedicated to the theme “The People of the Book,” I took part in a panel on disinformation organised by the Jewish Community of Livorno as part of their local programme of events. I was invited to bring my perspective from working closely with European institutions, digital platforms, and civil society on issues of hate speech, disinformation, and the prejudices that fuel them.

At first sight, disinformation1 may seem like an unrelated subject, perhaps too modern to connect to “the people of the book.” And yet, when we look more closely, disinformation is nothing but the shadow side of written culture: the manipulation of words, of knowledge, of stories. It undermines truth by twisting the very tools we use to seek it. What better antidote, then, than reading, inquiry, and the critical thinking that Jewish tradition has long placed at its core?

To illustrate to the audience how absurd, and yet powerful, disinformation can be, I shared a shark tale:

A few weeks before the event I was listening to one of my favourite Italian journalists and podcasters2, who told a story that has stayed with me. In 1989, off the coast of Piombino, a diver was killed by a shark in front of his son and a colleague. A shocking and tragic accident, yet only a few months after the event, rumours began to spread and even national television started to cover the case. Some claimed the shark attack had never happened at all, that the victim’s family had invented it in order to collect life insurance. Others suggested there had been an explosion, and that the diver was engaged in illegal fishing. Ridiculous as it sounds, the story was picked up by many, fueling suspicion and conspiracy theories. These conspiracy theories shifted the fear away from the shark, calming the collective “shark psychosis” just in time for the summer season to start. It took years for the truth to be restored and for the victim’s family to achieve some sense of justice, thanks to the thorough work of a journalist who, as a young reporter covering the story at the time, patiently pieced the facts back together3. It is an example of how disinformation works: it plays on fear, and on our very human tendency to cope with panic and apprehension by assigning blame4.

The story clearly resonated, and I could see many in the audience having an ‘aha’ moment as they connected it to their own understanding of how disinformation works. Stories like this one remind us that disinformation is not a new phenomenon. Jewish history offers painful evidence of this. In the Middle Ages, Jews were accused of poisoning wells during the Black Death or of using Christian blood in ritual practices — baseless charges that spread like wildfire and sparked violence5. Centuries later, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion became one of the most notorious pieces of fake news ever created: a fabricated text claiming to reveal a Jewish plot for world domination. Although exposed as a forgery over a century ago, it is still circulated today6. And in our own time, the same logic persists, just dressed in modern clothes: memes and conspiracy theories suggesting that Jews control banks, the media, or even the weather. And the latest news, believe it or not: apparently Jews are also behind the death of Charles Kirk (sic)7.

Moving from polarization to resilience: shifting focus to be part of the solution

The event itself took place in a small city: Livorno has around 153,000 inhabitants, yet its Jewish community today counts only 300-400 people. The contribution of Jews to the city over the centuries has been immense. Thanks to the Livornine laws8 of the late sixteenth century, which granted Jews exceptional freedoms and protections, Livorno became a thriving port and a place of flourishing trade, culture, and learning. During this year’s European Day of Jewish Culture, the community opened the doors of its synagogue and museum, and during the conference proudly presented a precious catalogue of ancient books, lovingly maintained and restored by the care and dedication of community volunteers. These volumes represent the ultimate proof of how deeply the life of the city and the life of its Jews have been intertwined for centuries.

The audience was composed almost entirely of older people, and almost all of them Jewish. Non-Jewish participants could be counted on one, maybe two hands. This is particularly striking given that the European Day of Jewish Culture is primarily aimed at non-Jewish audiences. Sadly enough, city authorities chose not to attend the event. Awareness of one another’s traditions and histories is the simplest path to countering unconscious bias and opening dialogue. It really is that simple.

Above all, what was missing were the young. Their absence is deeply felt in a context already marked by demographic decline. There are young people in Livorno who, most likely, will grow up without ever meeting a Jewish person face-to-face, knowing Judaism only through history books, or worse, through stereotypes and conspiracy myths encountered online.

That absence weighed on me and on many others in the audience I am sure.

Then came the questions from the floor. One person thought it appropriate to bring up Gaza – was it really wise to raise such a provocation in a tiny community that had just worked tirelessly to showcase centuries of local Jewish presence through the careful curation of thousands of books? And another participant, perhaps more hurtfully still, chose to diminish the testimony of antisemitism shared by a woman in the room: “Explain to me what this antisemitism really is!”

Moments like these reveal how fragile public space can feel for Jewish communities, even when the intention is to celebrate culture and learning. Yet both moments were handled through a respectful exchange: the panelists, myself included, argued politely, provided facts and offered perspectives the audience might never have considered before. In that in-person interaction we all felt validated and it felt good.

This is what polarization does: it narrows our view until every conversation is forced through the lens of division. And we replicate these dynamics in all areas of our lives. Online and offline, we retreat into echo chambers9, missing opportunities to connect, to listen, to stretch out an arm and engage with the complexity of the person next to us. The more polarized we are, the harder it becomes to understand one another, and the easier it is for disinformation to thrive.

At one point, an elder of the community proudly showed me the insults he had received on Facebook, along with his back-and-forth exchanges with the “hater.” He was animated, even satisfied at having stood his ground online. But I couldn’t help thinking: if we spend so much of our energy debating with unknown haters online, who is left outside engaging with real people? Might it not be a better use of our time to build dialogue in person, to bring back to the center of our work the decent people who want to improve the world around them?

In the end, what remained most palpable that day was the love and dedication of the organisers. The love for books, as living testimony of Judaism’s commitment to study. The love for memory, for transmission, for dialogue that insists on surviving even when it is hard.

Perhaps the deepest lesson to take home is this: to start again from that love. To let it guide us. In times as turbulent as ours, when disinformation and polarization thrive, we need new forms of allyship, unexpected partnerships, and the courage to imagine different ways of preparing for what is ahead of us.

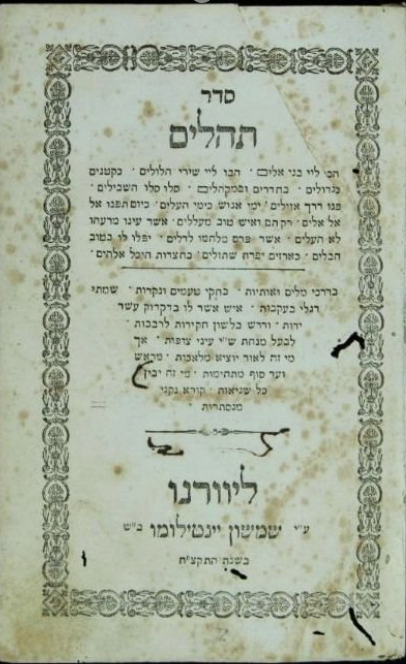

Tehilim, published in Livorno by the publisher Gentilomo, 1838

- https://commission.europa.eu/topics/countering-information-manipulation_en ↩︎

- https://open.spotify.com/episode/4Kq6VGmqrIlYEO7O0yGUj9?si=P8gMdkhISQm9BoXXHN754g&nd=1&dlsi=a2ac164b80384f72 ↩︎

- https://www.premioestense.com/2025/01/27/luomo-e-il-mare-storia-di-un-sub-ucciso-da-uno-squalo-e-dei-tentativi-falliti-di-ucciderlo-ancora/ ↩︎

- Psychologists call this the “negativity bias”: negative information has a far stronger impact on our brains than positive information, to the point where it takes around five positive experiences to balance out the weight of one negative one (Baumeister et al., 2001). ↩︎

- https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/fighting-hate-with-facts ↩︎

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sWLimSvxMq0 ↩︎

- No, I am not linking to conspiracy theorists’ websites and their social media pages! Instead, I’d suggest having a look at the wonderful collection of best practices to address antisemitism and foster Jewish life gathered by the NOA project: https://www.noa-project.eu/project/#” ↩︎

- https://www.livornotour.com/senza-categoria-en/livorno-ancient-city-of-nations.php?lang=en ↩︎

- https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/recommending-hate-how-tiktoks-search-engine-algorithms-reproduce-societal-bias/?utm_source=chatgpt.com ↩︎