CEJI Deep Dives: Algorithms

March 22, 2022

Amy Leete, Communications Officer

Ask most people what an algorithm is, and they’ll struggle to find an answer. It’s a term thrown around on the internet, often in relation to social media, but rarely defined in clear terms. In the simplest sense, an algorithm is a set of instructions that lead to a specific outcome. Algorithms are incredibly powerful. They stop planes crashing into each other in airports, they assign doctors and nurses to hospital wards, and even help our brains to figure out what coins to give a grocery store cashier. An easily understandable algorithm is a cooking recipe – the outcome is the cake, and the set of instructions is mixing the sugar and butter, adding the flour and eggs, and baking.

But what do algorithms have to do with social media? Computers are very, very fast at algorithms. The average laptop can perform 158 billion calculations a second. With 4.62 billion users a day on social media, humans alone cannot manage the sheer amount of data produced on social media sites. In the same way our brains use unconscious bias to help us process the 11 million pieces of information our minds are exposed to in any given moment, algorithms help cut through unending amounts of data and produce meaningful results. Companies like Meta (Facebook/Instagram), Twitter, and TikTok rely on computers to keep us online – to show us new content, or to let us search through our friends list, for example.

Why? The currency of the internet is attention, and there is only so much of it. Social media companies offer access to their sites for free, and make money through advertisement revenue. The longer we stay on the site, the longer adverts are exposed to us, and the more money they make. Social media companies therefore use a series of algorithms to discover what will keep us on their site.

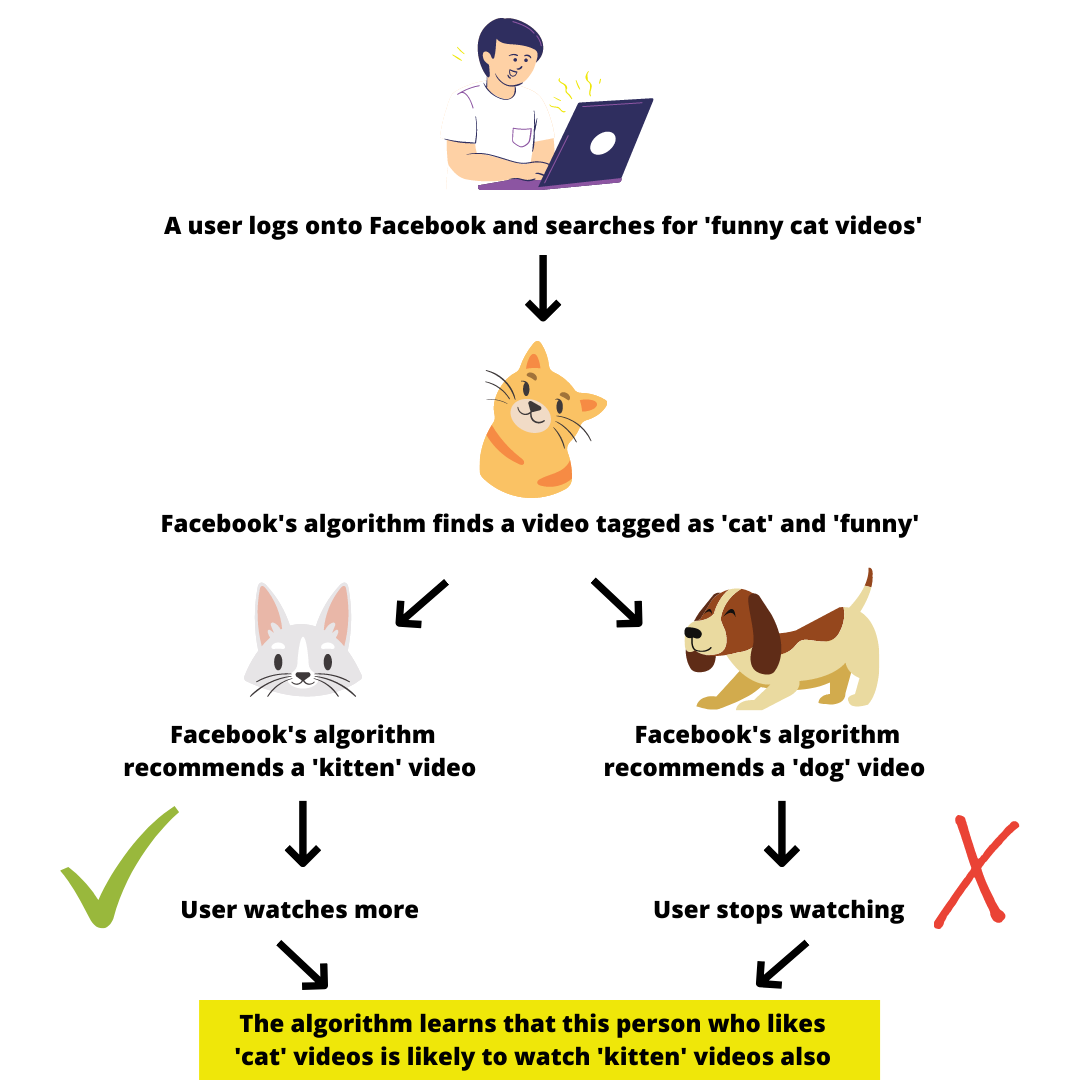

The example above shows how the algorithm uses our behaviour on the site to learn human behaviour – which can then be applied to the profitable advertisements shown to us. Watch a cute cat video on Facebook? Suddenly, Facebook will show you Amazon adverts for cat trees, new feeding bowls, or fun toys for kittens. Or perhaps you see an advert for Humane Society International, calling for donations to help cats in war zones. Companies, like Amazon, pay for those adverts to be shown to users who have already expressed an interest in that content.

Social media companies also use algorithms to monitor and remove hateful content. With Facebook alone removing over 10 million posts in the first quarter of 2020, the algorithm is a vital part of ensuring as much hate is removed from social media as possible. However, the very tool that removes hateful content is often the tool pushing it closer to people.

Unlike clearly inappropriate content, the biggest issue for algorithms is the borderline content that can lead to radicalisation. Algorithms, unlike people, are not good with context and nuance. For the algorithm, content is either removed by Facebook, or allowed to remain. If the content is allowed to remain, the algorithm will promote it to people who engage with content like it: cat videos are shown to those who have viewed cat photos before, conspiracy theory videos are shown to those who have viewed conspiracy theory photos. The very algorithm seeking to remove hateful content is often promoting content thatcan lead to extremist radicalisation. Tristan Harris, previously a design ethicist at Google, notes the implications of this model: ‘You can directly target a lie to the people who are most susceptible. And because this is profitable, it’s only going to get worse.’

The answer to hatred that spawns through the algorithm is simple in concept, but complicated in practice: teach the algorithm what bad content is. Algorithms are programmed by humans; we set the rules that the algorithms follow. By teaching algorithms the markers of content that are disruptive/divisive but not necessarily against site rules, algorithms can ensure this content is less visible. Machine-based learning allows us to do this. For some social media companies, this is already in place: Instagram already does so, by ‘reducing the spread of posts that are inappropriate but do not go against Instagram’s Community Guidelines.’ These posts will no longer be automatically shown or recommended to people, instead, you must actively search for that content, slowing the coverage it receives.

“We’ve started to use machine learning to determine if the actual media posted is eligible to be recommended to our community,” said Instagram’s product lead for Discovery, Will Ruben. Instagram is now training its content moderators to label borderline content when they’re hunting down policy violations, and Instagram then uses those labels to train the algorithm to identify them.

Yet, other social media companies remain quiet on the issue. Social media influencers often talk about ‘shadow banning’, a situation in which a user’s content is hidden or restricted from view without informing the user that it’s happening. ‘Controversial’ personalities online often argue that shadow banning is a way to control their freedom of speech. The last time Twitter talked about shadow banning explicitly was in this blog post from 2018 – stating that “people are asking us if we shadow ban. We do not.” However, they make it clear that ‘tweets from bad-faith actors who intend to manipulate or divide the conversation should be ranked lower[in search results].’ A rose by any other name would still smell as sweet.

Unlike other safety measures, such as teams of moderators, social media companies avoid talking about shadow banning for one reason: it makes the role of the algorithm clear. It places accountability on the shoulders of these companies, who have created the algorithm that shows hate speech. Above all, it allows users to understand how their daily experiences on social media are carefully and deliberately crafted by companies seeking to profit from our actions, behaviours, and desires.

In order to identify borderline content, or the markers of radicalisation within posts, social media companies must collaborate with experts in the fields, like CEJI. Social media companies must become transparent and honest about the effects of their algorithms on their users, and be clear about the steps they are taking – including shadow banning – to avoid potentially harmful content from reaching larger audiences. Conspiracy theories – often antisemitic in nature – push a narrative of ‘research’ and ‘enlightenment’, as if those who believe in them have broken away from the pack and have undertaken their own research. Uncovering the algorithm exposes this lie, and shows how content is fed to us for the sake of profit.

We often perceive social media sites as existing solely for us to communicate and keep in touch with friends and family, as we do not pay a financial contribution to use them. However, the algorithm model uncovers the profit-driven world of social media: and how our behaviour is constantly monitored and analysed so that machines can learn how to more effectively manipulate us. Understanding how, and why, social media companies are so keen to do this opens a more transparent discussion around how hate is cultivated online. On sites where we are constantly analysed by the algorithm, analysing the algorithm in return raises the accountability of social media companies on their role in fostering extremism and polarisation in an increasingly divided world.